The fifth death anniversary of Mr. Munir Ahmad Khan, Chairman of the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (1972-1991), who developed and led Pakistan’s nuclear programme for two decades and who achieved international recognition as a nuclear expert and advocate for the Third World is marked on April 22..

He spent his last days of illness in Vienna, Austria, where he enjoyed a distinguished tenure with the International Atomic Energy Agency (1957-1972). He was one of the first Asian scientists to join the IAEA, and rose to become director of the Reactor Engineering Division and Member of the Board of Governors, and was elected Board Chairman in 1986-87.

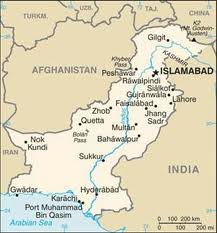

It was while he was still with the IAEA that Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto requested him to return to Pakistan as PAEC Chairman at the famous Multan Conference of senior scientists, where the foundations of the nuclear weapons programme were laid. It was a historic move as Pakistan thereafter embarked on a crash program to develop the atomic bomb, and he as the architect of the nuclear programme would make this dream come true by 1983 when PAEC conducted its first successful cold tests.

Under Munir’s dedicated leadership, Pakistan’s nuclear programme developed into a multi-faceted and dynamic center of science and technology, both on the peaceful and deterrence sides. He established the blueprint and developed the know how for Pakistan’s weapons capability. This includes the fuel and heavy water fabrication facilities, uranium enrichment and plutonium reprocessing facilities, nuclear fuel cycle facilities, training centres and nuclear power reactors.

In addition, the PAEC made formidable strides by developing new strains of rice and cotton that added billions to Pakistan’s agricultural output. Nuclear medical centres across the country have treated hundreds of thousands of cancer patients. Recently a long-standing dream of his was achieved with the elevation of the Centre for Nuclear Studies into an internationally recognised university. He established CNS as a centre of excellence, to provide the critical element of any nuclear programme, the trained manpower, which has so far produced over 2000 world-class nuclear scientists and engineers, at a time when the Western universities refused to allow Pakistanis into the nuclear field.

He initiated the Kahuta Enrichment Project, as Project-706, under Sultan Bashiruddin Mahmud, in 1974, two years prior to A.Q. Khan’s arrival in Pakistan. He completed the feasibility study, site selection for the plant, construction of its civil works, recruitment of the staff, and procurement of the necessary materials by 1976.

The PAEC under Munir remained in charge of the overall bomb programme, of all the 23 out of 24 difficult steps before and after uranium enrichment, and he continued to provide technical support to the enrichment program all along. The PAEC under him went on to develop the first generation of nuclear weapons in the 1980s. Munir started work on the bomb itself in a meeting called in March 1974, in which the secret ‘Wah Group’ was assigned the task of initiating work on it, prior to the arrival of A. Q. Khan in Pakistan.

The Chaghi tunnels were constructed under him and were ready by 1980. Munir successfully conducted the first ‘cold’ tests in March 1983, and the 1998 ‘hot’ tests were their confirmation. He made Pakistan acquire complete mastery over the nuclear fuel cycle, which is critical to the development and success of any nuclear programme.

The fuel cycle ranges from mining (uranium ore mining from mines), milling (uranium ore into yellow cake), conversion (yellow cake into hexafluoride gas, the crucial ingredient for uranium enrichment through the ‘gas’ centrifuge method used in KRL). Fuel fabrication (converting enriched uranium into uranium dioxide, sealing it into metal fuel rods and bundling into fuel assembly as fuel for nuclear power plants) was accomplished by PAEC under Munir.

Uranium enrichment would have been impossible without the hexafluoride gas, and mastery of the nuclear fuel cycle, which was accomplished by Munir. The highly enriched uranium is then converted into metal at PAEC and then into bomb cores, which itself involves very critical technologies, which were as great a challenge as uranium enrichment or plutonium reprocessing. Munir had laid solid groundwork for all these technologies, which enabled Pakistan to acquire nuclear capability by the early 1980s.

When in 1976 Canada suspended the supply of heavy water fuel and spare parts for the Karachi nuclear power plant, he took up the challenge and using indigenous resources produced the Feed for KANUPP, which is why the Muslim world’s first nuclear power plant is still running successfully.

He also upgraded the research reactor at PINSTECH and laid the groundwork in the 1980s for the 300 MW nuclear power plant at Chashma. Munir also laid the foundations of the National Development Complex, under Dr Samar Mubarikmand. Today NDC is a vital strategic organisation.

PAEC under Munir was also actively developing the plutonium programme, in spite of the cancellation of the French reprocessing contract, and went ahead with developing an indigenous pilot reprocessing plant, which was completed by 1981, known as the ‘New Labs’ in PINSTECH. The PAEC did not forego the plutonium route, and was successful at developing the indigenous plutonium production reactor at Khushab, commissioned recently. This was driven during Munir Khan’s 19-year tenure. Plutonium is used to develop advanced compact warheads, and makes more powerful bombs than uranium.

Munir was very modest, and shied away from the counter-productive boasting of his rivals. He saw Pakistan’s strength as lying in more than having a bomb, as equally dependent on a secure economic and political future and non-isolation in the world.

As he developed the PAEC programme, so too did he grow in international stature as one of the leading nuclear policymakers to represent Third World interests at international forum. A few years prior to his death, he was made Advisor on Science and Technology at the Islamic Development Bank to assist in developing their investment in the sciences in Muslim countries.

Munir Khan did his BSc from Government College Lahore as a contemporary of the late Nobel Laureate Dr Abdus Salam. He later went to the USA on a Fulbright Grant and Rotary International Fellowship where he earned a Master’s in electrical engineering from North Carolina State University and an MSc in nuclear engineering from Argonne National Laboratories in Illinois as part of the Atoms for Peace Programme.

Munir’s vision for Pakistan, and indeed the whole Muslim community, as a centre for science and technology, was an inspiration to scientists and colleagues around the world. The strict controls in PAEC from the time of Munir becoming Chairman in 1972 ensured that no financial bunglings or material ‘leaks’ would take place.

He was an example of how a scientist in a very senior and responsible position could behave with the utmost responsibility and secrecy in matters of supreme national interest. He was a man who was obsessed with secrecy, and believed that national security must be above personal whims and wishes, and abhorred personal aggrandisement. He spoke rarely to the press, and only in public, never in private, and he refrained from all self-projection and never indulged in cheap popularity stunts.

He never let any journalist in his office or residence, nor did he crave their attention. For all his sense of responsibility throughout his Chairmanship, he had to pay a personal price by remaining unsung. Some believed that keeping silent was a mistake, and that the people would never know of the accomplishments of the PAEC and his own contribution. He was deeply humble, impeccably honest and humane, an avid conversationalist who in the traditions of most nuclear scientists, was a connoisseur of arts, especially literature and Urdu poetry, particularly Ghalib, Iqbal and Faiz. And like most nuclear scientists engaged in changing the destiny of nations, he used to have long walks. He was a consummate conversationalist and burst into laughter without prodding. It was amazing how he had compartmentalised his mind. Manager of a colossal and highly sensitive nuclear programme, he talked of other things in the world without even giving a hint about his identity. His confidence and patriotism did not allow him to divulge his secrets to any man who did not belong to his trade.

With superabundant energy, iron will, and an intense patriotic zeal, he became a lodestar in the history of the nation. He was known as the ‘Father’ in PAEC circles, yet he remains an unsung hero whose contributions are largely unknown, and unacknowledged. His predecessor, Dr. I. H. Usmani, got the Nishan-i-Imtiaz posthumously after the 1998 nuclear tests, as did his successor, Dr Ishfaq Ahmed, yet he continues to be left out.

His detractors have been exposed in the recent proliferation scandal, and he stands vindicated. He remained associated till his last day in Pakistan with nuclear issues and continued to serve the country by sharing his rich 42-year experience in the nuclear field with PAEC even after retiring as Chairman in 1991. His greatest legacy is that he made Pakistan a nuclear power by making the nuclear programme independent of his self. Yet even five years after his death, he remains an unsung hero who along with his team of dedicated scientists and engineers enabled us to safeguard our honour as a nation. Justice requires that the falsification of history be rectified. The nation for which he lived his life, deserves to know the truth.

Courtesy: The Nation, April 22, 2004 (By M.A. SHEIKH)

He spent his last days of illness in Vienna, Austria, where he enjoyed a distinguished tenure with the International Atomic Energy Agency (1957-1972). He was one of the first Asian scientists to join the IAEA, and rose to become director of the Reactor Engineering Division and Member of the Board of Governors, and was elected Board Chairman in 1986-87.

It was while he was still with the IAEA that Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto requested him to return to Pakistan as PAEC Chairman at the famous Multan Conference of senior scientists, where the foundations of the nuclear weapons programme were laid. It was a historic move as Pakistan thereafter embarked on a crash program to develop the atomic bomb, and he as the architect of the nuclear programme would make this dream come true by 1983 when PAEC conducted its first successful cold tests.

Under Munir’s dedicated leadership, Pakistan’s nuclear programme developed into a multi-faceted and dynamic center of science and technology, both on the peaceful and deterrence sides. He established the blueprint and developed the know how for Pakistan’s weapons capability. This includes the fuel and heavy water fabrication facilities, uranium enrichment and plutonium reprocessing facilities, nuclear fuel cycle facilities, training centres and nuclear power reactors.

In addition, the PAEC made formidable strides by developing new strains of rice and cotton that added billions to Pakistan’s agricultural output. Nuclear medical centres across the country have treated hundreds of thousands of cancer patients. Recently a long-standing dream of his was achieved with the elevation of the Centre for Nuclear Studies into an internationally recognised university. He established CNS as a centre of excellence, to provide the critical element of any nuclear programme, the trained manpower, which has so far produced over 2000 world-class nuclear scientists and engineers, at a time when the Western universities refused to allow Pakistanis into the nuclear field.

He initiated the Kahuta Enrichment Project, as Project-706, under Sultan Bashiruddin Mahmud, in 1974, two years prior to A.Q. Khan’s arrival in Pakistan. He completed the feasibility study, site selection for the plant, construction of its civil works, recruitment of the staff, and procurement of the necessary materials by 1976.

The PAEC under Munir remained in charge of the overall bomb programme, of all the 23 out of 24 difficult steps before and after uranium enrichment, and he continued to provide technical support to the enrichment program all along. The PAEC under him went on to develop the first generation of nuclear weapons in the 1980s. Munir started work on the bomb itself in a meeting called in March 1974, in which the secret ‘Wah Group’ was assigned the task of initiating work on it, prior to the arrival of A. Q. Khan in Pakistan.

The Chaghi tunnels were constructed under him and were ready by 1980. Munir successfully conducted the first ‘cold’ tests in March 1983, and the 1998 ‘hot’ tests were their confirmation. He made Pakistan acquire complete mastery over the nuclear fuel cycle, which is critical to the development and success of any nuclear programme.

The fuel cycle ranges from mining (uranium ore mining from mines), milling (uranium ore into yellow cake), conversion (yellow cake into hexafluoride gas, the crucial ingredient for uranium enrichment through the ‘gas’ centrifuge method used in KRL). Fuel fabrication (converting enriched uranium into uranium dioxide, sealing it into metal fuel rods and bundling into fuel assembly as fuel for nuclear power plants) was accomplished by PAEC under Munir.

Uranium enrichment would have been impossible without the hexafluoride gas, and mastery of the nuclear fuel cycle, which was accomplished by Munir. The highly enriched uranium is then converted into metal at PAEC and then into bomb cores, which itself involves very critical technologies, which were as great a challenge as uranium enrichment or plutonium reprocessing. Munir had laid solid groundwork for all these technologies, which enabled Pakistan to acquire nuclear capability by the early 1980s.

When in 1976 Canada suspended the supply of heavy water fuel and spare parts for the Karachi nuclear power plant, he took up the challenge and using indigenous resources produced the Feed for KANUPP, which is why the Muslim world’s first nuclear power plant is still running successfully.

He also upgraded the research reactor at PINSTECH and laid the groundwork in the 1980s for the 300 MW nuclear power plant at Chashma. Munir also laid the foundations of the National Development Complex, under Dr Samar Mubarikmand. Today NDC is a vital strategic organisation.

PAEC under Munir was also actively developing the plutonium programme, in spite of the cancellation of the French reprocessing contract, and went ahead with developing an indigenous pilot reprocessing plant, which was completed by 1981, known as the ‘New Labs’ in PINSTECH. The PAEC did not forego the plutonium route, and was successful at developing the indigenous plutonium production reactor at Khushab, commissioned recently. This was driven during Munir Khan’s 19-year tenure. Plutonium is used to develop advanced compact warheads, and makes more powerful bombs than uranium.

Munir was very modest, and shied away from the counter-productive boasting of his rivals. He saw Pakistan’s strength as lying in more than having a bomb, as equally dependent on a secure economic and political future and non-isolation in the world.

As he developed the PAEC programme, so too did he grow in international stature as one of the leading nuclear policymakers to represent Third World interests at international forum. A few years prior to his death, he was made Advisor on Science and Technology at the Islamic Development Bank to assist in developing their investment in the sciences in Muslim countries.

Munir Khan did his BSc from Government College Lahore as a contemporary of the late Nobel Laureate Dr Abdus Salam. He later went to the USA on a Fulbright Grant and Rotary International Fellowship where he earned a Master’s in electrical engineering from North Carolina State University and an MSc in nuclear engineering from Argonne National Laboratories in Illinois as part of the Atoms for Peace Programme.

Munir’s vision for Pakistan, and indeed the whole Muslim community, as a centre for science and technology, was an inspiration to scientists and colleagues around the world. The strict controls in PAEC from the time of Munir becoming Chairman in 1972 ensured that no financial bunglings or material ‘leaks’ would take place.

He was an example of how a scientist in a very senior and responsible position could behave with the utmost responsibility and secrecy in matters of supreme national interest. He was a man who was obsessed with secrecy, and believed that national security must be above personal whims and wishes, and abhorred personal aggrandisement. He spoke rarely to the press, and only in public, never in private, and he refrained from all self-projection and never indulged in cheap popularity stunts.

He never let any journalist in his office or residence, nor did he crave their attention. For all his sense of responsibility throughout his Chairmanship, he had to pay a personal price by remaining unsung. Some believed that keeping silent was a mistake, and that the people would never know of the accomplishments of the PAEC and his own contribution. He was deeply humble, impeccably honest and humane, an avid conversationalist who in the traditions of most nuclear scientists, was a connoisseur of arts, especially literature and Urdu poetry, particularly Ghalib, Iqbal and Faiz. And like most nuclear scientists engaged in changing the destiny of nations, he used to have long walks. He was a consummate conversationalist and burst into laughter without prodding. It was amazing how he had compartmentalised his mind. Manager of a colossal and highly sensitive nuclear programme, he talked of other things in the world without even giving a hint about his identity. His confidence and patriotism did not allow him to divulge his secrets to any man who did not belong to his trade.

With superabundant energy, iron will, and an intense patriotic zeal, he became a lodestar in the history of the nation. He was known as the ‘Father’ in PAEC circles, yet he remains an unsung hero whose contributions are largely unknown, and unacknowledged. His predecessor, Dr. I. H. Usmani, got the Nishan-i-Imtiaz posthumously after the 1998 nuclear tests, as did his successor, Dr Ishfaq Ahmed, yet he continues to be left out.

His detractors have been exposed in the recent proliferation scandal, and he stands vindicated. He remained associated till his last day in Pakistan with nuclear issues and continued to serve the country by sharing his rich 42-year experience in the nuclear field with PAEC even after retiring as Chairman in 1991. His greatest legacy is that he made Pakistan a nuclear power by making the nuclear programme independent of his self. Yet even five years after his death, he remains an unsung hero who along with his team of dedicated scientists and engineers enabled us to safeguard our honour as a nation. Justice requires that the falsification of history be rectified. The nation for which he lived his life, deserves to know the truth.

Courtesy: The Nation, April 22, 2004 (By M.A. SHEIKH)